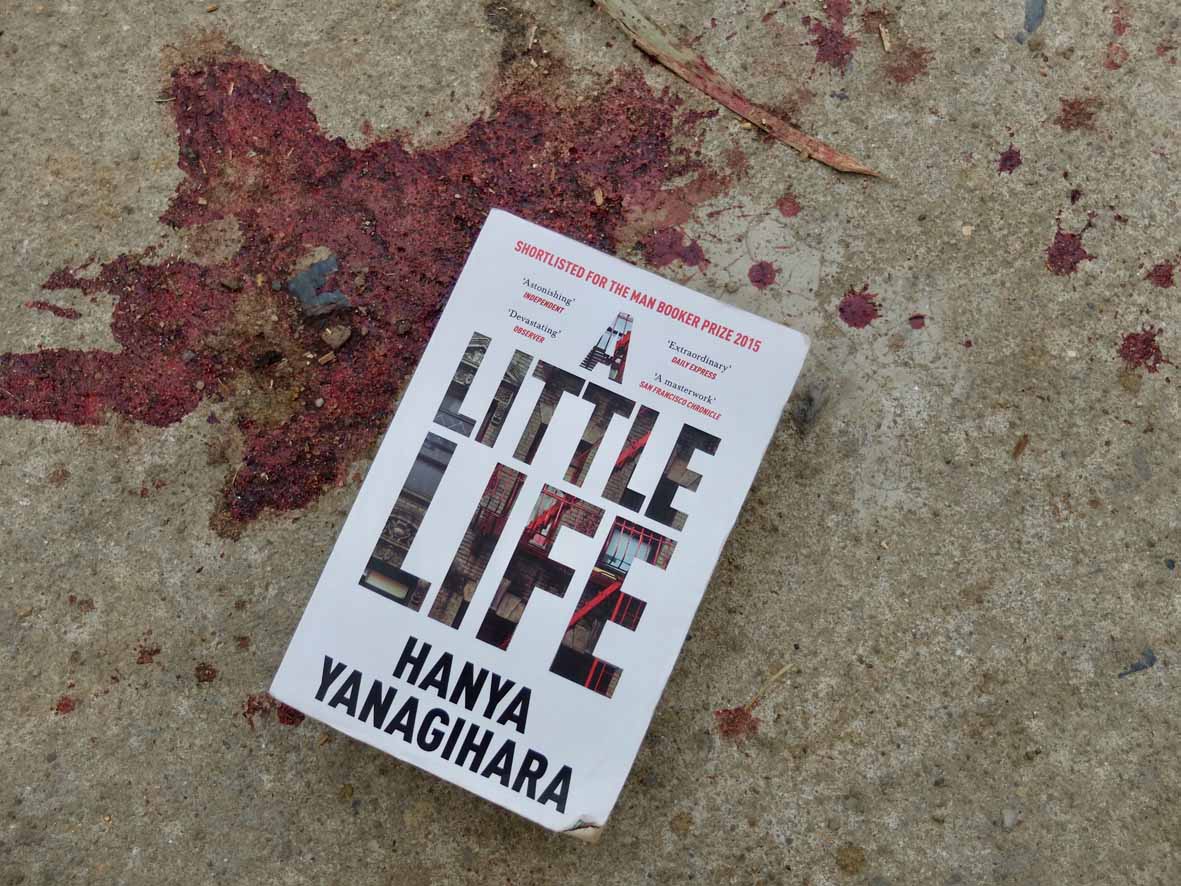

12 Feb ‘A Little Life’

‘A Little Life’ is an epic tale by Hanya Yanagihara. It documents the lives of a small circle of close male friends, over four decades. I began it with trepidation, wondering if I would be bored with the lives of four American students, who at first seem unremarkable. The story slowly wriggles beneath the surface of the characters to discover their emotional struggles. As their lives interweave, what unfolds is a detailed depiction of the repercussions of both physical and emotional abuse. The novel explores shame graphically. With relentless detail it describes pain and suffering. Sometimes it goes beyond the bearable as a reader, but that’s the heart of what Yanagihara is trying to show. She takes us into the landscape of survival and of disability. It is a remarkable telling, ambitious in scope, sometimes too dramatic. I wanted the protagonists to make different choices. It’s an excruciating read, but it stayed with me, and I wanted to know how it would play out. Through reading to the end, I found an empathetic understanding of the link between abuse and shame that I had known but never really ‘got’ before. It also delivers a visceral examination of self-harm in the wake of trauma. It twins inner misery with outer lives that are against type, which makes an interesting paradox. I think Yanagihara also explores the criteria to measure success – outward achievements, overcoming physical wounds, or the capacity to endure – and how best to respond and relate to those who hurt. It is not for the faint-hearted.

‘A Little Life’ is an epic tale by Hanya Yanagihara. It documents the lives of a small circle of close male friends, over four decades. I began it with trepidation, wondering if I would be bored with the lives of four American students, who at first seem unremarkable. The story slowly wriggles beneath the surface of the characters to discover their emotional struggles. As their lives interweave, what unfolds is a detailed depiction of the repercussions of both physical and emotional abuse. The novel explores shame graphically. With relentless detail it describes pain and suffering. Sometimes it goes beyond the bearable as a reader, but that’s the heart of what Yanagihara is trying to show. She takes us into the landscape of survival and of disability. It is a remarkable telling, ambitious in scope, sometimes too dramatic. I wanted the protagonists to make different choices. It’s an excruciating read, but it stayed with me, and I wanted to know how it would play out. Through reading to the end, I found an empathetic understanding of the link between abuse and shame that I had known but never really ‘got’ before. It also delivers a visceral examination of self-harm in the wake of trauma. It twins inner misery with outer lives that are against type, which makes an interesting paradox. I think Yanagihara also explores the criteria to measure success – outward achievements, overcoming physical wounds, or the capacity to endure – and how best to respond and relate to those who hurt. It is not for the faint-hearted.