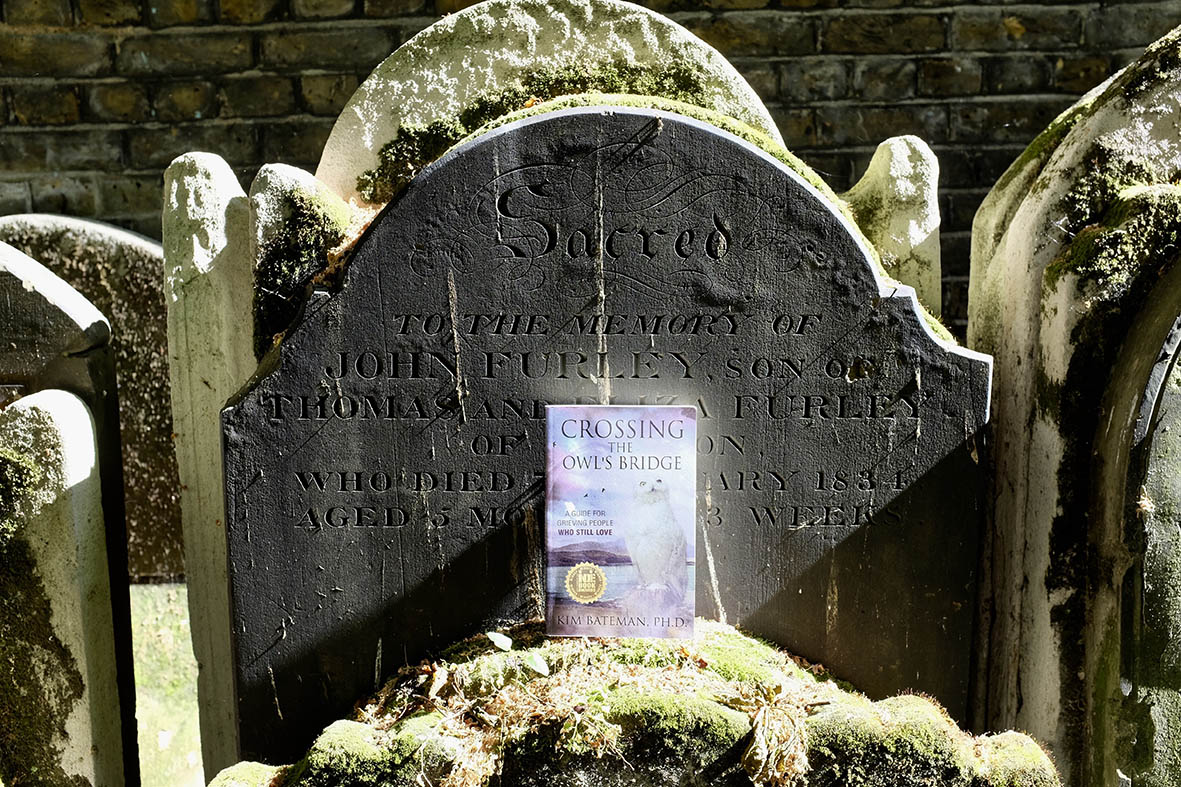

31 May Crossing the Owl’s Bridge

Kim Bateman’s ‘Crossing the Owl’s Bridge: A Guide for Grieving People Who Still Love’, is in itself a bridge between myth and real-life stories. With examples of folk tales from different cultures, Bateman takes us through the experiential processes that are shown symbolically in the narratives.

Kim Bateman’s ‘Crossing the Owl’s Bridge: A Guide for Grieving People Who Still Love’, is in itself a bridge between myth and real-life stories. With examples of folk tales from different cultures, Bateman takes us through the experiential processes that are shown symbolically in the narratives.

“As I began looking around at different cultures, and particularly their stories, I found that this theme of the loss of the physical coupled with a continued relationship in the imaginal is ubiquitous.”

Bateman correlates traditional tales with the stories of people who have experienced tragic losses and deep grief, and how they began their work of dealing with bereavement. Many of these short personal testimonies are heart-rending.

While grieving, the process she describes is for the bereaved to “create the symbols or rituals that you need to create a bridge – a bridge between you and your loved one.” This work of making-meaning, like the heroine Nyctea in one story, of bringing memories and mementos of a life together, can be helpful in actively coming to terms with, and changing the relationship with the person who has died.

Kim Bateman works with people who have lost their dear ones; she understands the initiation that bereavement can be. Her wise words come out of both personal experience, years offering grief work, and by listening to the sense below traditional folk tales. In the altered, liminal, non-linear grief space, myth and imagination can be really helpful tools to transform our relationships with the dead, whatever our beliefs.

She describes ‘Singing over bones’, which is also the title of her Tedx Talk.

“This mythologizing, or piecing together of memories, pictures, objects, among other things, is one of the ways in which the evaporated person takes form again.” I recognise this from the creative ways I have honoured my own ancestors’ belongings and histories.

Through acknowledging, being with, and tending to our losses, we may traverse through ‘the abyss’, and begin a journey of growing ourselves to be able to live with grief.

For our next Grief Tending events, please see here.