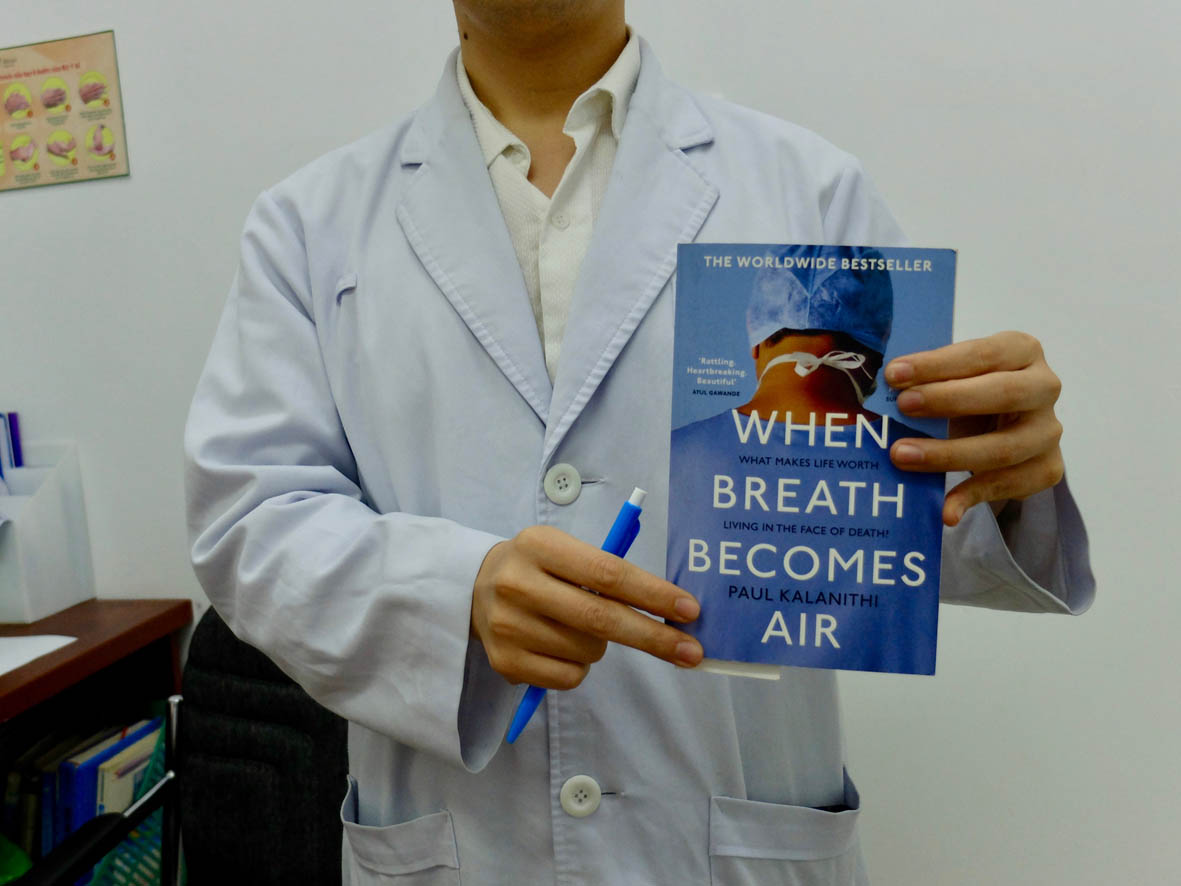

13 Feb ‘When Breath Becomes Air’

In his memoir ‘When Breath Becomes Air’, Paul Kalanithi writes with elegant clarity about his journey from euro-surgeon through cancer toward death. He writes with poignancy looking back at his life. First through literature, his family life, then medical training and neuro-science, he is “Seeking a deeper understanding of a life of the mind.” He struggles as a “Physiological-Spiritual Man” (Walt Whitman) to find a way, “that the language of life as experienced – of passion, of hunger, of love – bore some relationship, however convoluted, to the language of neurons, digestive tracts and heart beats.” A cancer diagnosis brings a different perspective to his life’s purpose as “the future I had imagined…evaporated.” He sees with new eyes as he experiences being the patient after years of being the doctor. He grapples to find, “What makes human life meaningful, even in the face of death and decay.” He seeks to act “as death’s ambassador,” to show us in both medical and human terms, “Here’s what lies up ahead on the road.” Kalanithi is unflinching in his portrayal of the feelings which make him afraid, frustrated and joyful. He says he “started in this career, in part, to pursue death; to grasp it, uncloak it, and see it eye-to-eye, unblinking.” This is a book about the responsibility those who care for us hold, and as a reminder for all those who will die. (If you think that’s not you, think again). He writes, “Before my cancer was diagnosed, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when. After the diagnosis I knew that someday I would die but I didn’t know when. But now I knew it acutely.”

In his memoir ‘When Breath Becomes Air’, Paul Kalanithi writes with elegant clarity about his journey from euro-surgeon through cancer toward death. He writes with poignancy looking back at his life. First through literature, his family life, then medical training and neuro-science, he is “Seeking a deeper understanding of a life of the mind.” He struggles as a “Physiological-Spiritual Man” (Walt Whitman) to find a way, “that the language of life as experienced – of passion, of hunger, of love – bore some relationship, however convoluted, to the language of neurons, digestive tracts and heart beats.” A cancer diagnosis brings a different perspective to his life’s purpose as “the future I had imagined…evaporated.” He sees with new eyes as he experiences being the patient after years of being the doctor. He grapples to find, “What makes human life meaningful, even in the face of death and decay.” He seeks to act “as death’s ambassador,” to show us in both medical and human terms, “Here’s what lies up ahead on the road.” Kalanithi is unflinching in his portrayal of the feelings which make him afraid, frustrated and joyful. He says he “started in this career, in part, to pursue death; to grasp it, uncloak it, and see it eye-to-eye, unblinking.” This is a book about the responsibility those who care for us hold, and as a reminder for all those who will die. (If you think that’s not you, think again). He writes, “Before my cancer was diagnosed, I knew that someday I would die, but I didn’t know when. After the diagnosis I knew that someday I would die but I didn’t know when. But now I knew it acutely.”