Posted at 16:48h

in

Sarah's Journal

by admin

Like Ash Sarkar who interviews Richard Beard on Novara Media’s podcast ‘Downstream: We Must Ban Private Schools’, I went to a comprehensive school. If this was also your experience, you’d be forgiven for thinking that ‘boarding school syndrome’ doesn’t affect you. Maybe like me you have friends or family who did, but it’s not just that. As Ash says,

“boarding school life is suffused through our popular culture,” and it creates a fascinating mystique, and consequences for us all. Of course, not everyone has a bad experience of boarding school life, and I’m not suggesting that if you went to a comprehensive school you had a brilliant time either. In an ideal world, education would be a flexible, caring, child-centred place to explore and develop.

Richard Beard argues (one of a growing cohort who have written on the subject including Joy Schaverien and Alex Renton), that boarding school is where many of our leaders in politics, business, law, journalism and other professions may have learned to disconnect from compassion. The consequences of the normalisation of separating children as young as seven or eight from their loving care-givers, to be imprinted by a competitive system that shames vulnerability, and where abuse, bullying and punishment were (in the past at least) endemic, may have repercussions for everyone in society.

This potentially traumatising system underpins much of our society, and was exported from the UK via colonialism to mete out further harm in other places. Beard adds that the values of this exclusive education also trickle down into the whole private school system in the UK, where “a cycle of entitlement” may be fostered, if people have been repeatedly told that they have received the best education. Beard eloquently describes a system that can condone independence, at the expense of distress, in the name of privilege.

Beard also describes the mechanism that creates this

“dislocation between what you’re being told and what you’re feeling”, which gives rise to repression of empathy. He describes the painful sound of a dormitory’s grief, where,

“a volley of cries goes round the room”, but “the next day we’ve got to get up and we’ve got to pretend that never happened.” The resulting internalised message is, “Don’t show empathy for other peoples’ emotions, and then don’t show empathy for your own. Don’t show empathy for your own sadness.”

Some of the other defences that people may be socialised into in this system include: deflection, politeness, charm and inauthentic self-deprecation. These defences compensate for a complex set of emotions that are being defended against. Richard Beard’s book ‘Sad Little Men: Private Schools and the Ruin of England’ explores these dynamics in public schools in more depth.

In artist Tony Gammidge’s animation ‘Norton Grim and Me’, he reveals himself as school boy in a dormitory where tears are ignored, and the severing of family ties is perpetuated in the name of tradition. He says:

“Norton Grim and Me is about my experiences of going to boarding school, aged 7 years old. It is about the trauma of the separation from my home and family, the tradition and culture that normalises this practice and the impact that this has had on me emotionally and somatically.”

It’s a short, powerful watch that gives an alternative version of boarding school to the jolly games of Quidditch in Harry Potter. Also disturbing is the portrayal of Philip and Charles’ school days as dramatic portrayals of a repressive regime in ‘The Crown’.

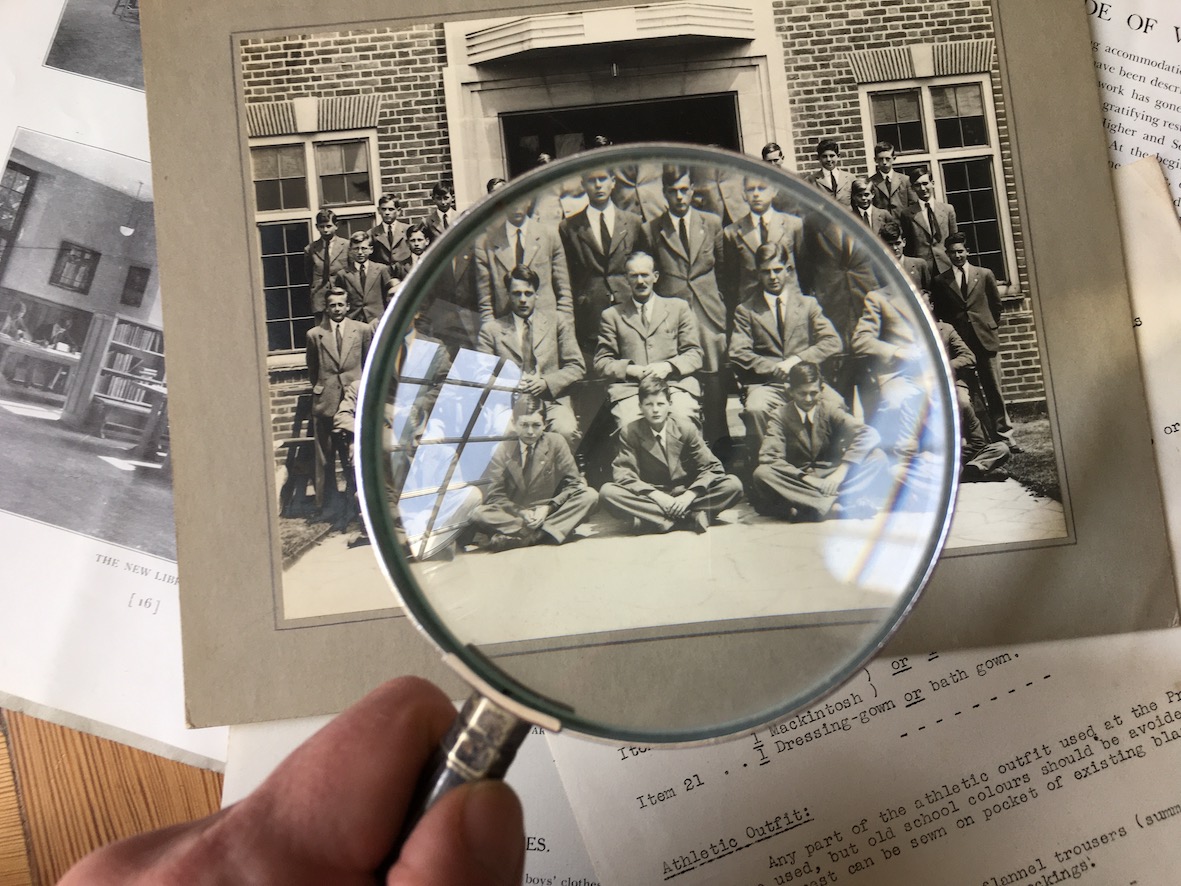

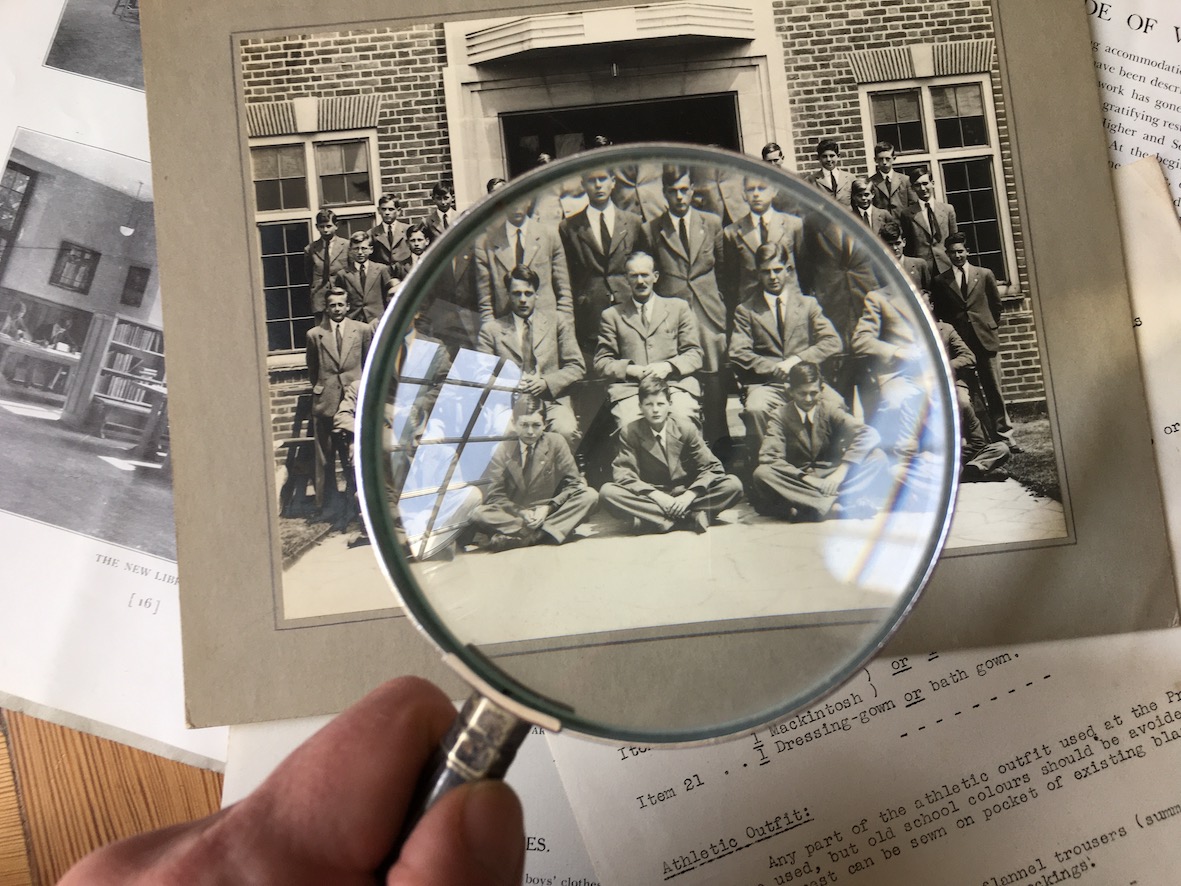

Rummaging in family papers, I find evidence from my father’s school days. I shudder when I read his school report age 8 that reads, “Has started Rugby. Will do better when he is a little more robust”. Even as an adult he remained slight. I scrutinise the faces of boys, the majority of whom look unhappy, and the stern ‘masters’.

In addition to the foundation provided by a boarding school education which may in itself be problematic, sexual abuse, at least in former decades was rife. I am gratified by Christ’s Hospital’s recent ‘statement of acknowledgement’, which feels like a significant step in the right direction. The Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry is currently investigating not only children in care, but also in boarding schools.

While individual teachers who are subject to allegations may face prosecution, the recognition that school cultures may have played a part in enabling or covering up harm that children in their care experienced is important. Boarding schools are one example of a ‘total institution’, as described by Erving Goffman. This is a “place of residence and work where a large number of like-situated individuals, cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time, together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life.” In such systems, if unscrupulous people are in charge, perhaps with their own developmental trauma, they can wield power unchecked with impunity.

Sophy Banks enquiry into ‘Healthy Human Culture’, looks at the dynamics of change in organisations. This work explores how we uncover the unhealthy dynamics that enables misuse of power, and how to begin the work of restoration and repair. Vitally she asks the question, what would a healthy system look like, with caring community at the centre, and educational values that favour respect, curiosity, creativity over ruthless competition?

In ‘Of Water and the Spirit’, Malidoma Patrice Somé describes his own religious schooling. It is an example of the way some Europeans exported an authoritarian educational regime. He rebelled,

“…for there are times when disobedience heals a very ailing part of the self. It relieves the human spirit’s distress at being forced into narrow boundaries. For the nearly powerless, defying authority is often the only power available.” His experience in this system was part of the process that eventually brought him back to his indigenous roots. This cross-cultural journey is one of the threads that would bring the social technology of Grief Tending to the UK.

Re-connecting with emotions, long repressed is a common theme that people may bring to Grief Tending spaces. Boarding school trauma, and other surrounding issues, may be a theme that someone carries. We offer support circles and grief workshops where we encourage empathy for both ourselves and others. You can find our next events here.

I’m paying attention to the invitations that come my way, and am saying “Yes” to some of the ones that in the past would have scared me. Now I am observing a little tingle and taking a risk.

I’m paying attention to the invitations that come my way, and am saying “Yes” to some of the ones that in the past would have scared me. Now I am observing a little tingle and taking a risk.