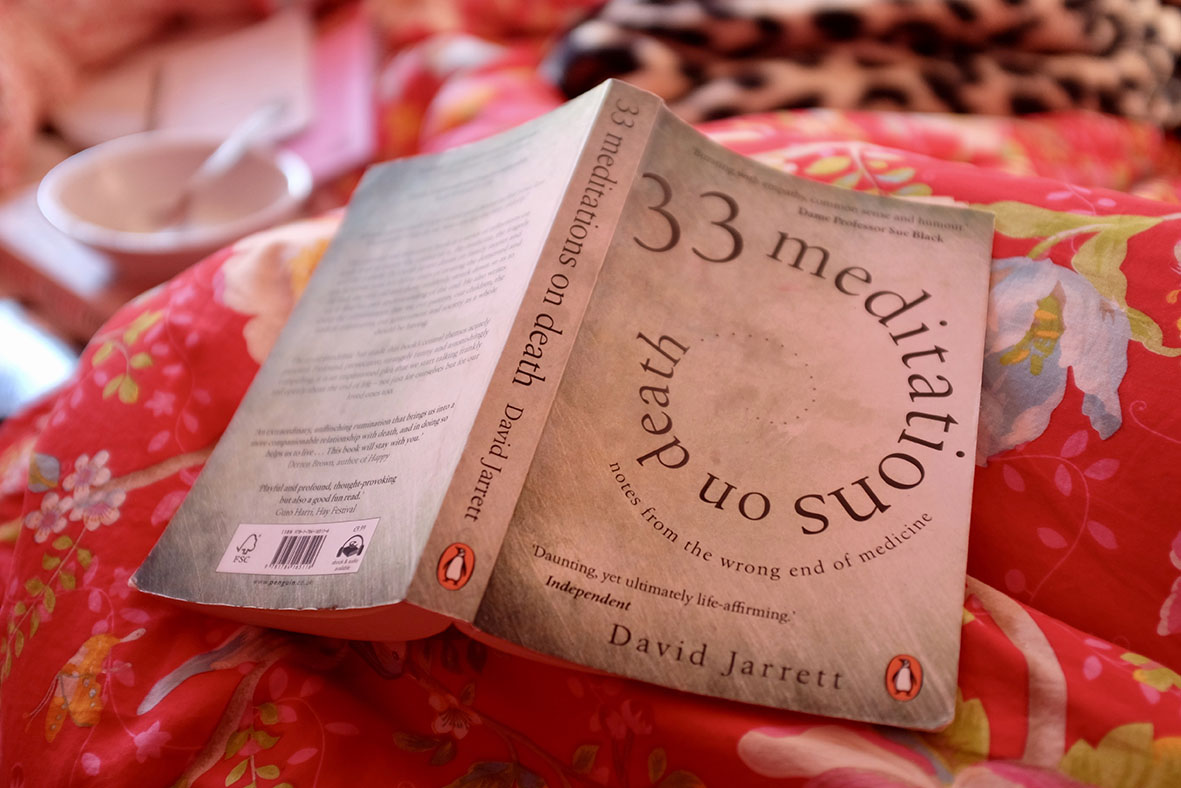

23 Mar 33 Meditations on Death

The second line appeared on my lateral flow test. I grabbed a few essentials from the kitchen and retired to bed. As symptoms circulated around my bronchial passages, I reached for ‘33 Meditations on Death: Notes From the Wrong End of Medicine’ by David Jarrett. Covid 19 does not appear until the final chapter, but contemplating age and vulnerability proactively are themes of the book.

David Jarrett MD is a long serving physician providing medical care to older people. If you are, or have been involved with the care of someone frail or elderly, you may already be aware of the medical ‘twilight zone’, the spectrum between life and death that older people can often fall into.

There is a great deal of sound thinking, alongside compassion and humour in the stories that come from Jarrett’s long service in geriatric and stroke care. “We are obsessed by mortality in modern health services, when we should be paying greater attention to quality of life. One is very easy to measure and the other virtually impossible,” he suggests.

Over a career that spans decades, we are given an inside perspective on the changes in medical practice, both for good or ill. We are treated both to the stories of patients, and doctors, who are dealing with mortality. It is a wise and engaging read, that brings insight to the perfect storm, “of longevity, prolonged infirmity and sheer numbers.” We are dying longer, as a consequence of living longer.

Some of the examples he brings have an element of tragicomedy about them, but in the face of uncertainty and the limits of medicine, the warnings he shares are important. Seventy is the new sixty for the lucky ones, see here for Advantages of Age who celebrate this.

However, there are wider implications to consider for us as ageing individuals. And for our collective greater good as a society, we need to debate these issues. As Jarrett says, “There is a burden of disease and there is a burden of treatment, and these two need to be balanced.” In his own words, “This is a call to arms for all of us to prepare and share more radical plans for our futures and perhaps in old age relinquish some of our considerable financial and electoral power.”

Sarah Pletts is a Grief Tender and Artist who offers workshops in London and online, sharing rituals where grief on all themes is welcome. For more information about Grief Tending events see here.