Posted at 13:17h

in

Articles

by admin

Learning how to feel

In dealing with grief, first we must learn how to feel our pain. Next, learning how to express our feelings is helpful. This takes practice, and may need support. In order to express your feelings you need to risk feeling vulnerable. In western industrialised society many have lost the skill of grieving well. Learning how to express your feelings is important when dealing with grief. The supportive environment of a grief tending group can help, in order to cope with loss.

“In the village, there is the belief that when anyone passes, no matter what their place in the community, something valuable to everyone is lost. Every death affects every person. Everyone grieves together. One thing that is often overlooked in the West is the importance of collective grief. When a death is not grieved by the whole community together, it leaves the individuals who were closest to the deceased shattered and alone. They end up without a path back to the life of the group.”

Sobonfu E Somé from ‘Falling Out of Grace’

Cultural resilience

We need to reclaim our feeling selves in order to come to terms with the difficulties we face as individuals and as members of a society. People in a healthy culture are connected to nature, to cycles of life and death and to each other. Through dysfunctional class, gender and educational norms, for many people it has been a coping strategy to learn how to hide your feelings. However, expressing feelings is a healthy way to start dealing with grief. Repressing our feelings can make them grow unmanageable and distort. Acknowledging loss enables us to become more whole physically, mentally and emotionally. Rather than avoid pain, when we allow it space it changes our relationship with it. Moving through our feelings helps us to deal with loss.

What is grief tending?

Essentially, ‘grief tending’ is giving time and space to tend to our grief in a group setting. It is a skill that can be learned to help when coping with grief. Being witnessed by a group can be powerful. Being part of a supportive group that comes together to do this work can be life affirming. Grief Tending may take place in an existing community of people, a group of people who come together temporarily to share this experience, or a group who meet regularly for an ongoing grief tending practice. In mainstream western society, dealing with grief is generally shared with a one-to-one counsellor at best, and at worst hidden away in private, solitary spaces.

What does the process involve?

The process usually involves a grief ritual where feelings may be expressed with or without words, framed by other activities. It may include words, but it is not solely a talking based practice. There is an arc of experience. At the beginning of the process the facilitators aim to build trust between group members. We call this ‘building the banks’. Then there is some exploration of the participants’ emotional landscape or ‘stirring’. At this point the group shifts into ritual space, where deeper expression may happen. Finally a period of integration or ‘soothing’ allows participants to shift gradually back to every day mode.

What’s the point of grief tending?

The aim is not to heal or fix grief. However, grief tending can be both healing and therapeutic. Grief tending is a practice where processing feelings can happen. During a session, there will be exercises that encourage participants to connect to positive resources, as well as gentle exploration into more uncomfortable feelings. It can also be a valuable tool in building resilient culture.

Grief tending is not an alternative to ongoing one-to-one therapy to deal with grief. These two ways of working complement each other. We encourage seeking one-to-one support in order to find continued support after a group session if necessary, especially if deep-seated emotions have been touched.

What is the benefit of grief tending?

In a relatively short time, grief tending can help someone to:

Deal with grief

Process feelings

Lighten their emotional load

Give access to joy and laughter

Bring connection with others

Surface buried emotions

Aid the process of clearing trauma

Bring a sense of perspective

Reveal the size and weight of grief

Expose numbness or disconnection

Open more to love

Connect with the cycle of life

Who is grief tending for?

Grief tending is for anyone dealing with grief and loss. This practice allows any loss to be felt and mourned. Every loss is meaningful. Many are familiar with responses such as shock, denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance following the death of a loved one. However, there is often less awareness of the difficulties that may accompany other kinds of change. A range of complex feelings can accompany any loss or ending.

What happens in a grief tending ritual?

There are different variations of grief rituals. The exact grief tending ceremony being offered will depend on the practitioner, the space where it is taking place, the time available and the number of people who are taking part. When we offer grief tending sessions, we try to find the most appropriate event format for the situation. We bring our own creativity, experience and strengths into each session. Alongside grief rituals, there will be a mix of embodied exercises that may include movement and relaxation.

Grieving with others may sound strange

Grieving with others may sound strange, but it can help to cope with loss. We encourage everyone to be themselves in a grief tending session. You will not have to do anything you don’t want to do in one of our workshops. We encourage participants to take care of their needs within the session. In a grief tending session you work with whatever issues come up for you. Supportive community can be hard to find. You will usually experience both being emotionally held by others, and being a part of that holding circle in a grief tending ritual. It may sound weird, but expressing feelings can be a relief. Participants are often surprised that it can also be fun. Building the connection between group members can normalise grief, and help to recognise the common feeling of shame around what they do or don’t feel.

In the eye of the storm?

Grief tending is not a first response method of help. If you are very recently bereaved, in the first throws of deep grief, this is probably not the time to work with grief tending. If your mental health is unstable, it is also unsuitable. Please seek advice from a health care professional if necessary.

Grief tending can be an excellent way of processing feelings. If you have been holding on to grief from the past it may be helpful. Perhaps you feel that you have got stuck in grief, and long to move through it. Working with grief in community can be a great tool if you want to explore a variety of themes, or just have a vague sense that grief may be lurking. If you are working with a therapist, grief tending can also help to surface material to explore more deeply in therapy.

Processing feelings is important

A wide range of feelings may be ready for expression. By identifying what may be present and how to express this, we learn skills that develop emotional intelligence. There is a growing awareness in therapeutic circles that processing grief is an important part of wellbeing. This may include complex grief or undigested emotions from the past. Grief tending as a tool for dealing with loss, also helps in building resilient culture.

Where does grief tending come from?

A number of different influences and teachings have come together in grief tending. Sobonfu and Malidoma Somé of the Dagara people originally brought rituals from Dano Village, in Burkina Faso to Europe and America. This included a traditional form of grief ceremony. Sobonfu Somé (who died in 2017) trained Maeve Gavin in grief tending in community. Our teachers Sophy Banks and Jeremy Thres worked with Maeve Gavin (who died in 2018).

Francis Weller (‘The Wild Edge of Sorrow’), Martin Prechtel (who was adopted by the Tzutujil people of Guatemala), and Joanna Macy (‘The Work that Reconnects’), are practitioners whose teachings and writings influence the work of many practitioners working with grief in community.

Bringing together ancient and modern

Grief tending brings together wisdom from both ancient and modern threads. Improved understanding around shame and trauma in clinical settings, mean that techniques are also developing for clearing and recovering from it. Experts in this field include Peter Levine, Stephen Porges, Carolyn Spring and Pete Walker. In grief tending we use ‘titration’, to touch in and out gently to grief. This is a trauma informed way to work with grief.

Is grief tending spiritual?

While some of the roots of grief tending may come from communities with shared spiritual practices, grief tending is non-denominational. Different practitioners will have their own flavour and personal belief systems. While participants of all faiths and none are welcome, the practice may include shrines, ceremonies, the elements, nature, and an awareness of something that is greater than us.

Finding a practitioner

Our own work takes inspiration from our teachers and the writings of many others alongside all that we have gleaned from our own creative and family lives.

If you want to find out more about the grief tending sessions we hold look here.

If you are looking for a practitioner, trust your gut instinct to find a person or practice that is appropriate for you in your current situation. Ask questions to find out more about their approach to dealing with grief.

Find some other UK practitioners here.

You can find some reviews of books on dealing with grief on our blog here.

Other sources of information and inspiration are on our links page here.

“We are designed to receive touch, to hear sounds and words entering our ears that soothe and comfort. We are shaped for closeness and for intimacy with our surroundings. Our profound feelings of lacking something are not reflection of personal failure, but the reflection of a society that has failed to offer us what we were designed to expect.”

Francis Weller

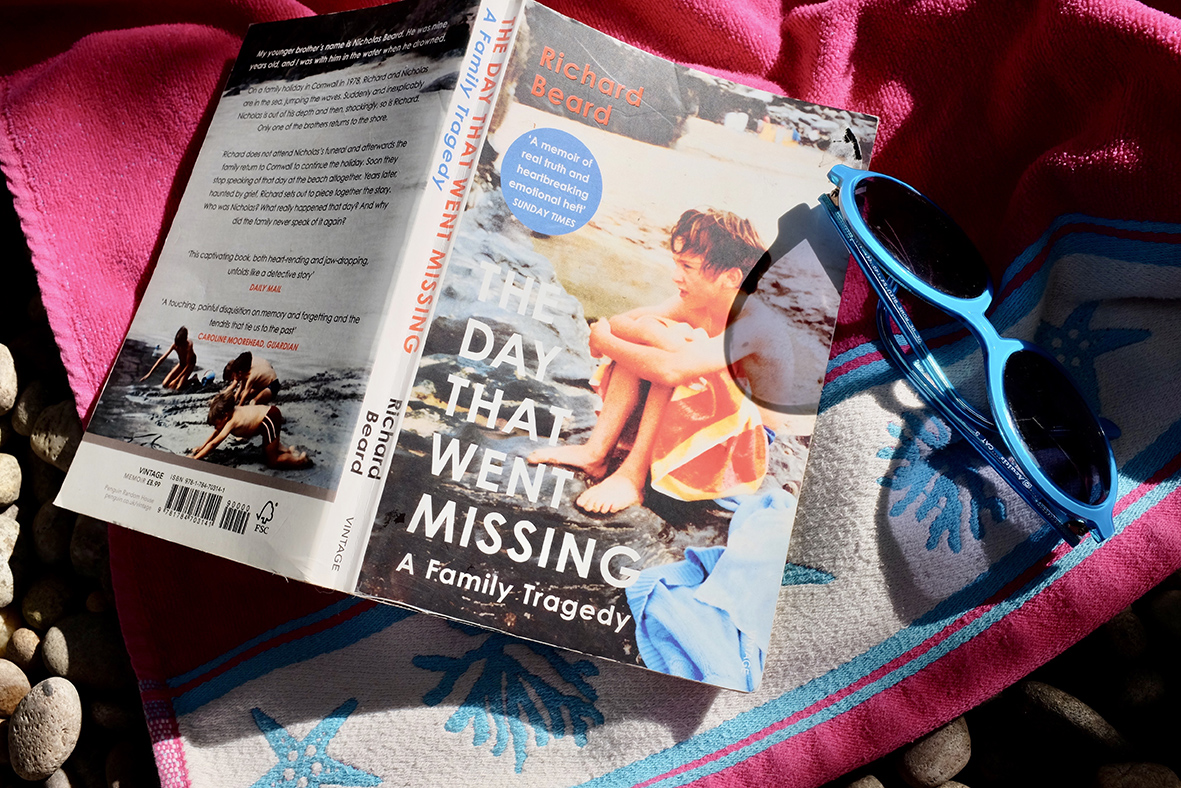

Richard Beard’s personal exploration of one tragedy in one family is also a tale of a very common survival strategy to avoid the pain of trauma. He unpicks threads in the circumstances that surrounded his brother’s death. In particular he begins to unwind linear ‘explicit’ memories of witnesses, and excavate more unpredictable ‘implicit’ memory fragments lodged in his body as “a definite physical memory.”

Richard Beard’s personal exploration of one tragedy in one family is also a tale of a very common survival strategy to avoid the pain of trauma. He unpicks threads in the circumstances that surrounded his brother’s death. In particular he begins to unwind linear ‘explicit’ memories of witnesses, and excavate more unpredictable ‘implicit’ memory fragments lodged in his body as “a definite physical memory.”