Posted at 14:37h

in

Articles

by admin

Why don’t we talk about menopause?

Why don’t we talk about menopause?

Why don’t we talk about the menopause? Are we just embarrassed to speak about personal things? Or is it because the things that happen to our bodies are loaded with shame? In talking about it, we might risk showing our vulnerability. We are loaded in western capitalist society by unconscious messages about beauty and mortality. Youth, productivity and fertility are valued markers of success, rather than wrinkles and wisdom. It may also be because approaching our senior years reminds people that they will not live forever, the truth we all try to forget.

How can we talk to our peers about menopause? Media images encourage women in particular to compete at looking younger for longer. Is it because we daren’t risk being rude or invasive that we don’t ask or reveal to one another? Talking about the menopause may be just one taboo in a long list. We may not have talked about the things that came before this rite of passage – puberty, bleeding, pain, lost pregnancies, infertility, terminations, tampons, fibroids, sexually transmitted infections, our sexual encounters, our sexual pleasure, masturbation…

The metamorphosis of menopause

Like puberty, you don’t know when the menopause will happen, and how it will land in your life. It is official a year after your final period. I see it effect the people around me in different ways. The most likely predictor for when it will happen is genetic. Early menopause can also come way before mid-life. This is less common, and is sadly much less widely recognised, as it arrives unexpected with many consequences. My final period came when I was 51, the average age, despite my first period being early. I now have a nostalgic fondness for copious bleeding and the earthy messiness of menstruation.

“Everything you cling to that’s comfortable in its familiarity including your very identity is metamorphosing from the inside out,” Christiane Northrup.

Up to 10 years of peri menopause

The piece of information I wish I had known ahead of time was that it may have a lead up of 4-5 or even up to 10 years of peri menopausal symptoms. Menopause can also come suddenly in response to surgical or medical situations.

Menopause used to be known as ‘the change’; as though it was a single turning point in the transition from the archetype of mother to crone. My experience has been of a gradual process of transformation. With hindsight I can recognise difficult and sometimes dramatic symptoms in a lengthy peri menopause.

During, or perhaps as a consequence of peri menopause I was exploring my sexuality, and I enjoyed surges in sexual energy. At the same time, I needed to come to terms with infertility. There was grief in being unable to be a biological parent. I gradually let go of dreams of being a birth parent. This came with an enquiry into who I wanted to become. I weathered the emotional shifts as my creative energy was channelled into other new ventures.

“Our hormones are giving us an opportunity to see, once and for all, what we need to change in order to live honestly, fully and healthfully in the second half of our lives.” Christiane Northrup

Navigating the changes of menopause

I was unprepared for the physiological changes. I did have encounters with medical professionals during gynaecological medical emergencies, but I found little information or support elsewhere. My mother couldn’t remember how old she had been by the time I got around to asking. There was a distinct absence of elders to pass on their wisdom on the subject.

Davina McColl’s refreshingly straight-talking documentary on Channel 4 ‘Sex, Myths and the Menopause’ is a good starting point on the subject. Information can be found on websites such as Women’s Health Concern – the patient arm of the British Menopause Society, Menopause Support and Menopause Matters. Look for independent reliable information that is not covert advertising for products, treatments or consultants.

There is still stigma and embarrassment in talking about menopause issues. Like other signs of mortality, talking about ageing can be taboo, worse still showing visible signs of it. I am aware that some people feel more invisible in the face of the physical changes of becoming mature. Others may redirect their energies into new endeavours with vigour.

The issues around menopause are not just ‘women’s business’. In a mission to make menopause more inclusive, Tania Glyde recognises that ‘Queer Menopause’ effects many including women, trans men and non-binary people. Whatever your identity, it is likely to include hormonal, physiological and emotional changes.

Menopause in Relationships

Friends, family and partners may be in different life phases, or moving towards elderhood in different ways. It may be complex to co-navigate changing needs and desires in lifestyle and relationships. After many years caring for others, I found myself with more time to invest in new interests that I hope will sustain me into the next phase of my life.

Coming to terms with changes in levels of desire, or response may precipitate exploration into what works for us sexually. If you haven’t already considered what you still want to receive, or give, I recommend Betty Martin’s ‘Wheel of Consent’. Being menopausal doesn’t mean we have to give up on intimate touch, although it’s a great time to work out what we do want to share in relationships with others.

A rite of passage

Like most rites of passage, the route through menopause is a liminal journey of stages – preparation, threshold and return. Ideally there will be support and education during peri menopause, and adjustments made before the final period. The threshold occurs, but we may not know it until a year after it has happened. One of the things that I found tricky was not knowing when I had actually had my final period. There was a gap of six months and then a year between my penultimate and final periods.

During this time, we will be aware that our years of potential fertility or procreation have come to an end. As with any big life change, this transition is an opportunity to grieve what is ending. Our ability to recognise and face this letting go process will reflect how we feel about our achievements and regrets as our identity shifts. The health concerns that may have accompanied our menstruation cycles will also be factors.

As physiological changes happen, are we welcomed into a community? Do we have support in place for this new time of life? Do we have peers we can talk to? Is our GP willing to hear and respond to our concerns? Are we resourced enough to find the support we need to manage symptoms?

After all the changes that may accompany peri menopause, and then menopause, I notice an absence of marking this initiation. Will our arrival on the shores of eldership be acknowledged or better still celebrated? Is this the time, or will I have become a member of the older generation when my hair turns white, or when there are no longer any family members ahead of me?

The symptoms of menopause

There are many symptoms that may be part of the experience of menopause. Hot flushes, (hot flashes), poor memory, changes in sexual responses and vaginal dryness have affected me. Then there are night sweats and early morning anxiety which disrupt my sleep patterns. Symptoms may arrive suddenly or gradually then ease off or stick around.

I have experimented with a variety of alternative treatments to support my physical and emotional health at different times including Chinese herbs and Acupuncture, Grindberg Method, Cranial Osteopathy, Herbal Medicine and natural bioidentical hormone creams. This is in addition to taking food supplements, good nutrition and exercise. My family enjoyed regular yam patties for a while. Yam is one source of naturally occurring oestrogen, but quite an effort to mash.

One solution to ease vaginal dryness

If you want to avoid the graphic details of my journey with vaginal dryness, stop reading here. Vaginal dryness crept up on me, and I became reluctant to engage in penetrative sexual play until I discovered that regular activity in my vagina actually made the pain improve rather than worsen. I retreated from the dread of the words ‘vaginal atrophy’ by putting some practical steps into action.

Experimenting to find what works for me, I now have a daily practice of repeatedly inserting and removing a ribbed glass dildo into my vagina. You can find a selection at Women’s ‘adult emporium’ Sh! and other adult stores including Love Honey. This stretches my vaginal sphincter and helps my vaginal walls to lubricate. I use a dollop of ‘Yes VM’ natural organic vaginal moisturiser. (Their lubes are great too.) Over time I built up to moving swiftly in and out for a couple of minutes. Now I do it about 70 times every morning just before brushing my teeth. When I began, this was an unimaginable goal. But it has over time reversed the pain and dryness which I was experiencing during intimate touch.

Anything that enhances blood flow to the pelvic area may help. Practices of self-pleasure that work for you are worth experimenting with. I find ribbed glass good for stimulating and stretching, and the glass has a cooling sensation. I wish someone had given me a few tips, so I hope this will be useful information to pass on.

On the other side of menopause

What am I like several years on from my last period? A more direct communication style has replaced some of the buffers of ‘niceness’. I am more confident in who I am and what I want to do. My gender identity also feels less fixed, and also less important as my hair greys. Brain fog and memory lapses can make me feel at the edge of my capability, but I feel as though I have no time to waste, ready to offer my experience to the world as an elder in training.

My inexpert experiences here are a kind of coming out, to reveal what often remains unseen and unheard in the shadows. I value intergenerational work. The conversations I have with the extraordinary young people I come into contact with fill me with hope. The generations have such different perspectives and exposure to ideas around sexuality and the body. In writing this I offer an invitation to risk having conversations about the nitty gritty of life with elders and youngers alike.

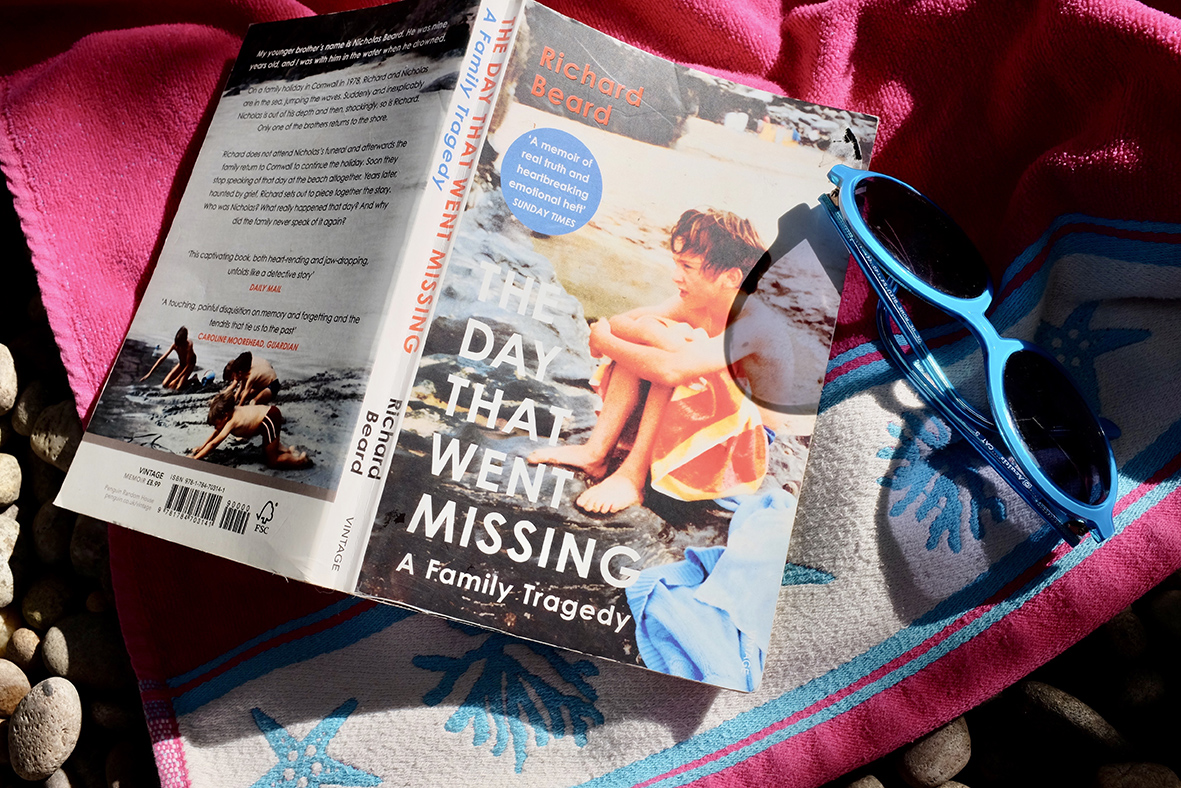

Richard Beard’s personal exploration of one tragedy in one family is also a tale of a very common survival strategy to avoid the pain of trauma. He unpicks threads in the circumstances that surrounded his brother’s death. In particular he begins to unwind linear ‘explicit’ memories of witnesses, and excavate more unpredictable ‘implicit’ memory fragments lodged in his body as “a definite physical memory.”

Richard Beard’s personal exploration of one tragedy in one family is also a tale of a very common survival strategy to avoid the pain of trauma. He unpicks threads in the circumstances that surrounded his brother’s death. In particular he begins to unwind linear ‘explicit’ memories of witnesses, and excavate more unpredictable ‘implicit’ memory fragments lodged in his body as “a definite physical memory.”